Uncle Lou Gatanas Story

Within every industry, every discipline, every art form, and every hobby, there are the experts; the famous gurus and know-it-alls whom everyone looks up to. Sometimes there’s a bunch of them, and sometimes there’s only a few. But what you’ll find, if you’re dedicated enough to your craft to sift through the noisy layers of information, is that usually the most well-known experts are actually standing on the shoulders of giants.

As you’ll inevitably discover if you stick to your passion long enough, there is another layer entirely: what I like to call the “experts’ experts;” the true masters of their crafts. These are the people you might not hear about immediately after getting into a new space; these are the people that the gurus go to when they get confused; the people who inspired these gurus in the first place; the ones who really do know almost everything: the giants.

Uncle Lou Gatanas is one of those giants, and it was a pleasure to get the chance to talk with him about his world and his passion: the Gibson Les Paul.

Hello Uncle Lou! Tell us a bit about yourself. What’s your story?

I’m a first-generation Greek-American. I was born and lived my entire life within a 7-mile radius of Queens, NY. I come from a large family with lots of siblings, and we grew up in a humble, lower-middle-class neighborhood. My siblings and I didn’t know we were poor; we figured everyone had their lights or phones turned off occasionally.

I’ve worked as a paperboy, delicatessen stock boy, dishwasher, delivery boy, and counterman in my brother-in-law’s burger joint “Jackson Hole NYC.” In the mid-1970s, I picked up skateboarding and was a total badass, going semi-pro and doing exhibitions in the Tri-State area until about 1981, when skateparks all over NY suddenly closed in favor of roller skating. Upon graduating high school, I worked with my dad as a general contractor until I eventually went out on my own—and this was around the same time I got into guitars.

In the early ‘90s, I produced a multi-platinum-selling comedy album with The Jerky Boys, and then in 1994, I formed Uncle Lou’s Classic Guitars, Inc., and the rest, as they say, is history! By the way, notice how I’m leaving out my Kluson tuner replacement tips? That’s another whole story, and I prefer not to be known as the ‘tuner tip guy’ anyway!

How did you get involved in vintage guitars?

I started playing guitar in 1980 when a few of my high school buddies formed a band. I thought it was the greatest thing ever—why just listen to your favorite music when you can actually play it yourself?

My first guitar was a cheap POS Les Paul Special copy with a bolt-on neck. It was horrible and impossible to tune, but I was saving my money to buy a Les Paul like my hero Jimmy Page. The first song I learned from start to finish was “Stairway to Heaven” through a combination of chord charts in a book and playing along with the record. After a while, I could play the song pretty well, but I didn’t even bother trying to learn the solo; I was convinced nobody in the world but Jimmy Page could play it! All the local bands I’d seen who attempted that song always butchered it beyond recognition, which confirmed my theory!

Around this time, there was this older, long-haired guy named Gary Masters living in my building. He owned a little Triumph TR6 sports car that I used to jump over with my skateboard (that’s a whole other story!) One day my girlfriend told me she’d heard he plays guitar and was looking for students, so I rang his doorbell. He confirmed the rumors and invited me inside with my POS fake Les Paul Special, which he couldn’t tune for me either! So, as we were chatting, I sarcastically asked if he knew the solo for Stairway To Heaven. He said yes, but was completely preoccupied with trying to tune my guitar to some degree. It was at that moment I decided “Pfff…this guy is so full of s#!t, only Jimmy Page can play that.”

But after a minute or two of messing around with the POS, he put it down and picked up his Stratocaster, which turned out to be a 1971 sunburst, with a 4-bolt maple neck. Then, with this unplugged Strat, he played the Stairway to Heaven solo perfectly, note-for-note. My jaw hit the floor and my eyes popped out of my head; I had just witnessed the impossible. And he did it without any effort or fanfare, like he’d been playing it all his life, no big deal. But to me it was everything—so our lessons began with that. Over the next few months, he taught me a few other songs and solos as well, usually just from memory; he didn’t even need to play along with the records.

He always mentioned he wasn’t crazy about his Strat, because he preferred rosewood boards. So as a token of my appreciation for everything he taught me, I took my Les Paul savings and went down to Manny’s (a nearby music store) and bought a brand-new rosewood board Stratocaster for him. He refused to accept it at first, but after an hour he decided to trade me his maple-neck Strat for it. Perhaps I could sell it and buy a Les Paul, he reasoned.

It’s now spring of 1981. My family had moved to a house across town, and I’m sitting on the front stoop playing my 1971 sunburst, maple-neck Strat. My new neighbor, Ricky Raven, correctly identified the guitar as he was walking by. I confirmed his guess, and he told me about his guitar collection from the 1960’s, back when he used to play. After checking out Ricky’s stuff, which included a ‘66 Telecaster and an old Rickenbacker 365 in natural finish, I instantly recognized that older guitars were better and just very cool to collect. Ricky and I went on countless guitar-buying safaris over the next few years, and he’s pretty much responsible for putting me on the path I still follow to this day.

How do you describe your profession? What services do you provide, and how can our readers reach you?

I always tell people I’m an antique guitar dealer, just to lend some degree of credibility to what I do, the reality of which is basically seven-day weekends, but on-call 24/7 and always ready to do a deal at a moment’s notice.

I buy, sell, and consign high-end ‘50s and ‘60s vintage Fender and Gibson solid-body electric guitars and parts. I maintain a website, but in regards to actually posting items for sale, I’m most active on Facebook. I also occasionally list items on eBay.

The best way to reach me is via email: unclelou59@gmail.com.

Who are your customers?

The majority of my customers are doctors, lawyers, and Wall Street types; boomers who couldn’t afford these amazing guitars during the ‘50s & ‘60s, when they were new. And now that these folks are financially secure at this point of their lives, they want closure; they want the guitars of their youth that they were denied, the very same guitars their heroes played and used to record the music they still love today.

I also deal with a fair number of rockstars, most notably Metallica. I’ve been dealing with them and became friends with them ever since the mid-to-late 1990s. I also deal with a large number of players and collectors in need of original ‘50s and ‘60s parts, either for restorations, conversions, or custom builds.

How many Bursts have you owned throughout the years? And out of all of them, which one really sticks out for you?

I’ve been through over 140 original Bursts since 1986 when I got my first ‘59 Burst (serial number 9 0710) from Southworth Guitars. It was a cute little guitar with nice color, and both sides were covered with the skinniest flames I’ve ever seen, each like 1/16th of an inch wide, and seemingly hundreds of them! I paid about $6,500 for it at the time and sold it for $10,000 a few years later. That was the moment I realized I could actually make a living doing this. The whole detailed story is actually a good read and worth a look. It can be found in the book Burst Believers II by Vic DaPra.

I’ve had plenty of mind-blowing examples of Bursts throughout the years, and I’ve flown as far as Australia to get a Burst deal done. But if I had to pick only one, it would be the JBL/Spinal Tap Burst, it’s where my obsession with Bursts began. I first became aware of this guitar in a JBL speaker ad in a guitar magazine in the early ‘80s and it was the proverbial “love at first sight.” I knew my hero Jimmy Page played a 1959 Les Paul, so therefore I needed one too—but being penniless at the time was problematic. The bottom of the ad read, “1959 Les Paul, serial number 9 0823, courtesy of Norman’s Rare Guitars, Reseda, CA.” So, I got the number from directory assistance and made a “long-distance phone call” in the days when it was a big deal, and expensive! I got Norm on the phone, and he explained that he still owned the guitar, but it wasn’t for sale. So, having balls of steel, I simply told him if he EVER decided to sell it, to PLEASE give me a call (I said this despite being penniless, which was unbeknownst to Norm), and he graciously agreed…probably just to get rid of me!

Many years had passed, and I had already been through a fair number of Bursts when I got a most unexpected phone call out of the blue. It was Norm. He told me he was ready to sell, but he wanted CrAzY MoNeY for it — six figures! To my knowledge, nobody had ever paid six figures for ANY vintage guitar, other than the Brock Burst (9 0913)—but that doesn’t count since it was a private deal between the seller and a multi-billionaire that never affected the rest of the Burst market. Anyway, I didn’t want to tell Norm I didn’t have that kind of scratch, so I asked him to give me five minutes to make a call. I immediately called a heavy-hitter buddy of mine, who immediately said YES. Then I instantly called Norm back, telling him “DONE DEAL.”

After getting the financing together in the craziest way anyone has ever heard of, I hopped on a plane to LA to complete the deal on my buddy’s behalf. I sure was relieved when the guitar arrived intact, and my boy was thrilled with his purchase. But better still, the guitar was “in the family,” and I knew one day he would eventually sell it to me. That day would come many years later when my boy called me quoting a price higher than any vintage guitar had ever sold for in history, but I didn’t care. I said yes, and this time I had the bread to get the deal done.

Sadly, after waiting much of my adult life to own that guitar, I didn’t have a minute’s peace during the six months I owned it. EVERYONE was busting my balls 24/7 to buy it off of me. So, I decided the best way to get people off my back was to quote the Mother Of All “F**k-You” Prices on it. Unfortunately, as staggering as that amount was, it sounded reasonable to the very first person I quoted it to, and just like that, the guitar was gone. It took two years for the rest of the Burst market to catch up—but now, in today’s market, it’s probably worth three times that amount. Life lesson: shooting from the hip can sometimes end with shooting your own foot.

Tell us about the Bursts in your collection today?

These days I only own two Bursts. Both are from 1959, with nice color and strong flame; they represent the “Alpha and Omega” of Burst collecting: where it started, and where it ended up.

The ‘Alpha’ guitar is an old-school Burst with a SICK top that’s been well-known in the Burst community and lusted after for decades. It’s affectionately known as “Ouch,” serial number 9 1854. This was a working man’s guitar, and it shows the modifications typical of the ‘60s and ‘70s (Grovers, frets, and Bigsby), but it also has a repaired headstock as well. In the old days, nobody cared about all that “baggage;” flame was everything, and mods like that were commonplace and widely accepted. Then everything started changing in the late ‘90s; people started valuing originality in the same league as flame, which old-school guys like myself considered insane.

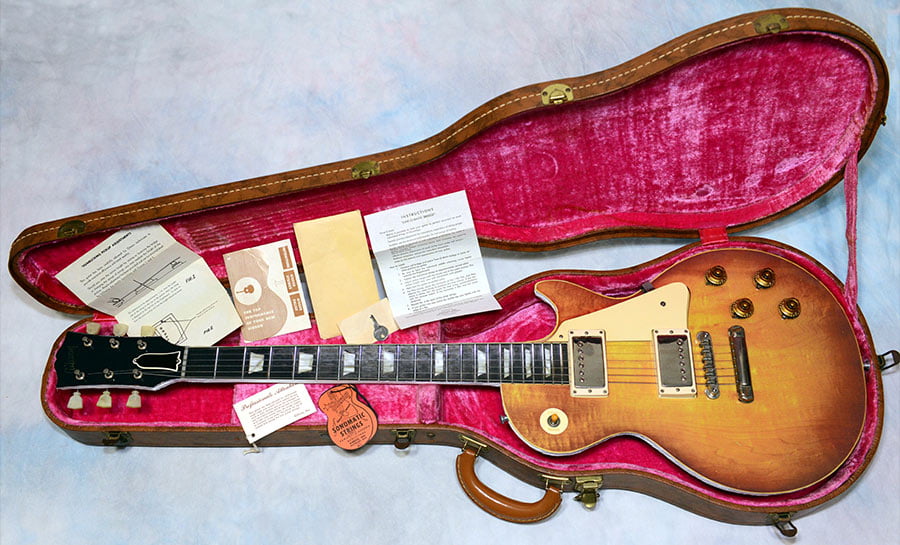

This brings us to the “Omega” guitar, an unmolested, no excuses, highly flamed ‘59 with strong color, in mint condition with tags (serial number 9 1972). It’s a guitar that nobody can say anything negative about. I actually had a tough time finding a guitar like this. The majority of Bursts out there have been modified at some point; so finding a 100% unmolested Burst these days is like finding a virgin in a brothel.

Why do you think Bursts weren’t hugely popular when they first came out, and what makes them so highly sought-after by collectors and musicians today?

Bursts were way ahead of their time in the late ‘50s. Rock ‘n’ roll was in its infancy, and Strats were the weapon of choice. Hard rock, electric blues, and metal weren’t even on the radar yet, but when music shifted in that direction, the proper tools were already available: maxed-out tube amps and older Les Pauls with humbuckers. Bloomfield and Clapton were among the first to figure that out. Today’s players and collectors love those old recordings, so naturally, they want to same equipment their heroes used.

Do you think Gibson could conceivably create a guitar today that sounds as good as a Burst?

I don’t think it’s possible to recreate the magic of an original Burst given today’s production methods and wood supply. But many years ago, I was involved with Edwin Wilson, formerly of Gibson’s Custom Shop, on a potential project: “Burst Clones,” the mother of all reissues. I had access to old-growth Honduran mahogany and eastern hard-rock maple, and so at that point, my inventory of original Burst parts could only be rivaled by someone with access to the Gibson Kalamazoo plant in 1959 via time machine.

The idea was to build a dozen Bursts out of old-growth wood using original production methods and materials (glue, lacquer, etc.), and original 1959 fittings, fretboards, and cases. These would’ve essentially been the equivalent of refinished originals; old wood, old parts, and new paint. The target retail price was north of $100,000! Unfortunately, that project, like so many others I mapped out with Edwin, never came to fruition. I ended up selling my entire parts inventory piecemeal over the years.

How do you verify the authenticity of a vintage Gibson Les Paul?

Just because a person spends all their time watching home-improvement shows on cable TV, doesn’t mean they can go out and become a contractor. Likewise, someone who spends all their time on Google and reads every Burst book ever published, but has never held a real burst, basically knows d!*k. There is absolutely no substitute for many years of frequent hands-on experience, examining both real and fake guitars.

The way I examine a Burst begins with a “vibe check”. When you’ve been doing this for as long as I have, guitars tend to give off a vibe. Righteous guitars give off good vibes the moment you open the case; you just know they’re right. Likewise, goofy guitars give off bad vibes and get your Spidey sense tingling; they literally creep you out.

Next, I give a quick visual check to make sure everything is as expected and there are no breaks, cracks, touch-ups, changed parts, etc. Then my nose gets involved and I take a good sniff here and there in search of “wrong” smells. This is the preliminary exam and it takes about five minutes. By this time, I’m usually pretty confident with my verdict. It’s crucial to get your chops together enough to make a determination after only five minutes because sometimes that’s all the time you get—like when you’re doing a Burst deal in the parking lot of a Burger King.

When time constraints aren’t an issue, that’s when a full examination takes place, with screwdrivers, blacklights, and powerful magnification. Every single screw, all the hardware, all the plastic, the wiring, pot codes, the solder joints, the finish, EVERYTHING gets thoroughly examined. It’s critical that you have as much experience with fake guitars as real ones—just because solder joints look old, doesn’t mean they’re original. Likewise, a finish that “lights up” under a blacklight isn’t automatically original. Master forgers can replicate these features to some degree, and only a well-trained eye with lots of experience and attention to detail can distinguish between “original” and simply “looking old.”

What advice would you give to someone who is considering purchasing a vintage Gibson Les Paul?

Bring an expert with you to evaluate the guitar BEFORE you buy if you’re not 100% confident you know what you’re looking at. Never buy anything you’re unsure of, even if you’re expecting someone knowledgeable to look at it afterward during a 48-hour approval period. If a seller is shady enough to sell you a goofy guitar, chances are you will not be refunded in a timely manner—if ever!

Which do you prefer: P-90s or PAF Humbuckers?

I know a lot of people love P-90s, but I’ve got no time for those. When I’m in the mood for single coils, I’ll play a Strat. For me, there’s nothing like the “macho tone” of a 1950s PAF Les Paul through a maxed-out Tweed Bassman or Twin Amp. I honestly have as much fun playing a muted chunk-a-chunk rhythm or power chords that sustain forever as I do playing a solo. I’m all about the chunky macho tone, and PAF Les Pauls deliver every time. I do have one caveat, however: disembodied PAFs are only as good as what you put them in. In the same way, you can’t expect to have a great vegetable garden by planting seeds in wet concrete, you can’t expect PAFs to turn a certified POS into a great guitar.

Will we see “Burst-in-a-Box” again, or is that no longer possible?

“Burst-in-a-Box” is a riff I’ve never heard before. The first time I displayed a complete set of parts for sale, properly positioned (as much as possible) in an empty case, people called it the “Ghost Burst.” Years later, I took it up a notch and snapped a photo of my Mark Reale “Riot” Burst (9 0314) and enlarged the photo to life-size. I then had it mounted and laminated on foam board. Next, I carefully cut it out with an X-Acto knife and mounted all the parts in their proper positions. I called it “The CardboardCaster.”

In the late ‘80s to early ‘90s, I started a trend that’s very popular today but was unheard of back in the day: “parting out” guitars. I would buy any basket-case Strat: routed, refinished, broken, etc., as long as the neck was original and most of the parts were present. I found I could actually pay full retail price for these guitars and still turn a 50% profit after selling off all the parts and cases. I didn’t think there was anything morally wrong with what I was doing; the guitars I sacrificed were beyond restoration. But the parts that came from these could restore nearly-intact guitars back to original.

My stash of Strat parts was so vast, that if someone asked me for a ‘63 pot, I’d reply, “What week of ‘63 do you need?” But during all the years I did this, I would also buy every Burst part I could find and stash them. To keep things in order, I’d begin with a brown Lifton case and a checklist, then slowly put in all the required parts to complete a set. Every screw, every piece of metal, plastic, and wire. It was basically a Burst after a colony of termites got through with it. And every time I finished a set, I’d open another brown case and start another set. I never sold any of the Burst parts, as it was like a hobby/investment for me—Strat parts and vintage guitars were my main gig. At one point, I had 17 complete sets of Burst parts in brown cases, but that wasn’t good enough. I sold off all the 4-latch cases and replaced them with proper 5-latch Liftons. I wasn’t fond of “Stone” or “Cali Girl” cases. I also decided all my sets should have double white PAFs, so I upgraded all my sets with those and ended up with tons of double blacks and zebras kicking around. Then I married all the cleanest parts with the cleanest cases, and got original sets of tags and case candy for them. You can’t even imagine what a staggering amount of time and money this “hobby” cost me.

After many years of doing what I was doing, I pretty much got out of the Strat parts biz, and started moving the Burst parts. The problem was, very few people needed a $70,000 set of Burst parts. This was part of my motivation for working with Gibson on the failed “Burst Clones” project. The lack of interest from buyers prompted the dismantling of complete sets—so there’s really no reason to start assembling them again.

In your opinion, is the Gibson “Burst Years” shipping ledger information out there for people in the know, or is it really still missing?

Throughout my 40+ years of doing this, it was always common knowledge that the Gibson shipping ledgers had a large gap from approximately mid-1958 through 1960; this period was commonly referred to as “The Burst Years.” With the remaining ledgers before and after fully accounted for, it seemed pretty obvious to me that the most crucial ones were stolen, hidden, or possibly destroyed. I never knew or heard of anyone with access to that information, no matter who they were or who they knew, the information was not available to anyone.

Then Gibson recently put out a no-questions-asked reward for the return of those ledgers, and “something” magically appeared. I never actually saw the books, just random samplings of pages that did not resemble existing late ‘50s pages—they looked more like the 1960s ledgers, so I was very skeptical and dismissed it as fugazi. Let’s face it: a $59,000 reward is all the motivation shady characters would need to “create” these long-lost ledgers.

Which guitars have a more versatile tone: ‘57 all-Mahogany Goldtops, or Maple Caps?

I’ve owned many ‘57 maple-cap PAF Goldtops in the past, and currently own a near-mint ‘57 all-Mahogany PAF Goldtop that I got from Kirk Hammett as part of a trade for a ‘59 Burst I sold him. I know everyone says they aren’t as bright as the more common Maple Caps, but if there’s any difference, it’s not obvious to me. It’s got all the tone and sustain I need.

But before people go hating on Mahogany Goldtops, here’s something to consider: do people prefer a one-piece or three-piece bodies on Les Pauls? Doesn’t a single slab of wood vibrate differently than a slab with two glue joints? Mahogany-body Les Paul Standards and Les Paul Custom bodies are carved from a single, thick slab of wood; they don’t have Mahogany caps, and certainly not two-piece caps. In a word…touché.

What do you do for fun?

Ask anyone what their favorite holiday is, and you’ll get varied responses such as Thanksgiving, Christmas, Hanukkah, Easter, Passover, Groundhog Day, etc. But if you ask me, without hesitation I’d respond, “July 4th”. BBQ, beer, fireworks; is there anything more fun?

In 2018, I decided to lose my “weekend warrior” status and go legit. I attended a few training seminars, passed the required exams, and I now work for two different world-renowned fireworks display companies that have been in continuous operation in the USA since the mid-19th century.

I now have my own company as well, having attained my NYC, NYS, and Federal ATF pyrotechnician’s licenses. I can now legally purchase and shoot commercial-grade, professional fireworks. My company name is Sky Painting by Uncle Lou, Inc.

Share your thoughts in our forum! 💬

👉 Introduce yourself and show off your Les Paul and other gear.

Share this post with your friends using these one-click sharing options:

👉 Click here to share on Facebook.

👉 Click here to share on Twitter.

👉 Click here to share on LinkedIn.

Get the latest reviews, guides and videos in your inbox.